Bobby Heenan In WCW: "The worst six years of my life"

Bobby ‘The Brain’ Heenan. Arguably the most outstanding manager in the history of the sport. Certainly one of the most quick-witted minds to ever step foot in a wrestling company. The partnership on commentary between The Brain and his best friend, Gorilla Monsoon, is legendary. For an entire generation of wrestling fans, when they think of the WWF, they picture Hulk Hogan facing off against Andre The Giant, with Bobby Heenan in his corner. He was intrinsically aligned with the idea of the WWF for nearly a decade and was well-loved by all those who worked with him. So what would lead him to leave the leader in the world of sports entertainment for a job with their main competitor, World Championship Wrestling?

At the tail end of 1993, following some turbulent years in the WWF, thanks to the much-ballyhooed steroid trial and the sexual assault allegations, Bobby had come to a point where his passion was dwindling. He was rarely working with his friend Gorilla Monsoon anymore, and the travel was beginning to get to him. According to Bobby in his autobiography Bobby The Brain – Wrestling’s Bad Boy Tells All, things went a little sideways when it came time to renew his contract.

My WWF contract was up in 1993, and Vince McMahon gave me an offer for a new contract. A week later, he told me that he couldn’t honor that offer and wanted me to take a 50 percent pay cut. I didn’t want to do that. I was tired of going to New York, tired of crowds, and tired of people. It was just hard to get around. I decided it was time to go.

Due to how beloved he was and his tenure with the WWF, Bobby got to leave the WWF on his terms, being dragged out of the building by his old partner, Gorilla Monsoon and thrown into the cold. Of course, it was Bobby’s idea because he knew his role and how his character was perceived.

Shortly after leaving the WWF and deciding to stay home with his wife Cindy, the telephone rang with Eric Bischoff on the other end. But it wasn’t simply the money or a desire to work that made him go to WCW, as he again described in the book.

I got a call from Eric Bischoff at WCW, and he made me an offer to work one day a week for the same money Vince had offered me. At that time, my daughter Jessica was going to the University of Alabama. I lived in Tampa and would work in Atlanta, which was only 200 miles from her. Once a week, I could go up and see her for lunch. That’s why I took the job with WCW.

Heenan made his WCW debut in January of 1994 at the Clash of Champions, of course, with a humorous introduction via Mean Gene Okerlund. But while he appeared thrilled and happy to be there on camera, nothing could be farther from the truth. As someone who had come up through the rigid territories and worked under the likes of Paul Boesch, Verne Gagne and others before spending nearly a decade with the WWF and Vince McMahon, WCW was, in effect, a clown show.

One consistency Bobby brought to WCW was that he always kept his distance from Hogan because of their ongoing feud from the eighties in the AWA. Even when Hogan turned heel in WCW, Bobby didn't root for him because he wanted to protect the business.

When looking at Bobby’s estimation of his new employer, he only dedicated one relatively brief chapter to the six years he spends with WCW. That alone is a damming revelation, but he does break down quite a bit about the discouraging environment in his estimation.

At one point, he brings up trying to pitch Eric Bischoff an idea, to which Bischoff more or less tells him that Heenan, a man who is recognized as an excellent mind for what gets over or draws, is being paid to call the matches and not pitch ideas. Needless to say, it was the only time that Heenan tried to help out creatively.

After production meetings in the WWF, Vince McMahon would say, "Let's go have some fun." In contrast, after WCW production meetings, they would say, "Let's go see if there's any free food left." However, upon arriving, Bobby often found that all the food had already been consumed.

Personnel from production usually walked by without ever saying hello. Bobby described that the atmosphere in WCW was akin to a city of the living dead, with minimal communication and a lack of camaraderie among colleagues.

In Bobby’s view, he also had a tumultuous relationship with nearly all of his commentary cohorts. While he never says anything about working with Dusty Rhodes beyond a humorous anecdote while working the Road Wild PPV events, he was not so kind with his other cohorts. Speaking of Steve McMichael, he felt that as good a physical athlete he is, he was on the completely another end of the spectrum when it came to commentary. He also felt he could have attempted a similar vibe to his commentary with Gorilla regarding Lee Marshall but realized no one would buy The Weasel bowing up to Marshall only to back down.

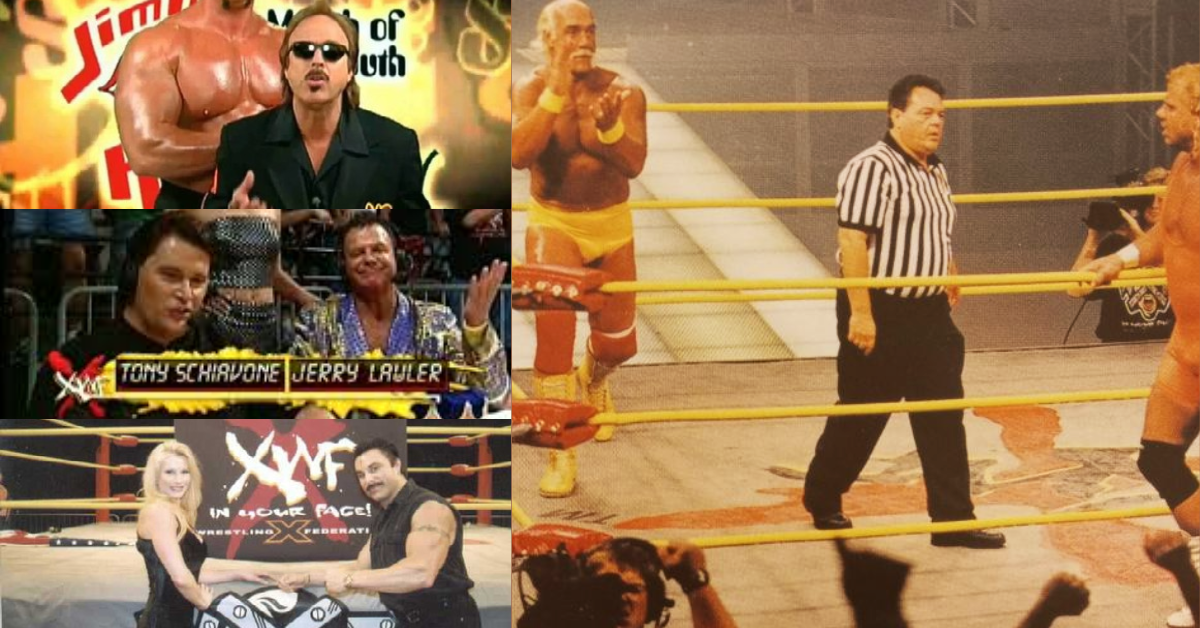

These anecdotes pale compared to how he felt about Tony Schiavone, a man he felt he could not trust despite his best efforts. According to Heenan, Schiavone was usually the only one who had an inkling of what was to come on the show (while also revealing that many shows would be on the second or third match before they received their formats for the show) and would constantly say “knowledge is power.” Heenan felt like Tony used this to his advantage and eventually gave up on having a relationship with his peer.

Mike Tenay was the only fellow broadcaster (not including Mean Gene Okerlund or Dusty) that Heenan shared good thoughts on. Giving him incredible kudos on his vast wrestling knowledge, Heenan found in Tenay the one person he could bounce off of at the desk. Essentially, Heenan would talk a lot of smack and go on and on until Tenay could use his knowledge of wrestling and linguistic skills to put Bobby in his place. Sadly, Tenay seemed to be the only one he liked, even going so far as to call the man who would replace him on commentary, Mark Madden, as a slob from Pittsburgh.

These bad experiences, in addition to who knows what else Bobby chooses not to elaborate on, make it relatively easy to see why he considers his tenure in WCW the absolute worst in his long prestigious career in professional wrestling. This, of course, becomes even sadder to realize that this was his last major run. He returned to call the Gimmick Battle Royal at Wrestlemania X-Seven in 2001 before being inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2004, giving one of the most memorable and loving induction speeches ever.

But despite all the negative, Bobby Heenan did leave an overall positive legacy with his time in WCW. Bobby’s arrival in 1994, joining Mean Gene Okerlund, gave WCW much-needed credibility. If one of the most beloved personalities felt it worth being in WCW, they must be doing something worth watching, right? And that’s not even touching on some of his iconic calls that are still being played to this day in video packages. His call, “We are at war!” helped boost the New World Order story to legendary status.

Yes, digging deeper and discovering how miserable his time in WCW was puts a damper on his time there. But for the common wrestling fan, especially of a certain age, Heenan’s work in WCW is timeless and maybe even what they are more familiar with than his territory or WWF work. And that certainly has to mean something.